中医药是打开中华文明宝库的钥匙,李时珍中医药文化是这个伟大宝库中一朵璀璨的奇葩。传承和传播中医药文化,对弘扬中华优秀传统文化、增强民族自信和文化自信,促进文明互鉴和民心相通都具有极其重要的意义。《“十四五”中医药发展规划》《中医药振兴发展重大工程实施方案》等国家政策文件对新时代中医药的开放发展和对外交流事业都做出了长远的规划,作为推动中医药文化创造性转化、创新性发展的重要形式,中医药翻译和传播已受到全社会的广泛关注。为进一步弘扬和传播中医药文化,促进中外文明的交流互鉴,提升中国国际话语权,在前四届“时珍杯”全国中医药翻译大赛的基础上,由世界中医药学会联合会李时珍医药研究与应用专业委员会、中国翻译协会医学翻译委员会携手举办“第五届‘时珍杯’全国中医药翻译大赛”,为构建人类卫生健康共同体贡献更大的力量。

指导单位:中国外文局翻译院、中华中医药学会翻译分会、湖北省翻译工作者协会

主办单位:世界中医药学会联合会李时珍医药研究与应用专业委员会、中国翻译协会医学翻译委员会

承办单位:湖北省翻译工作者协会医学翻译委员会、湖北中医药大学中医药国际传播研究中心

支持单位:上海文化贸易语言服务基地、传神语联网网络科技股份有限公司、中语智汇科技(厦门)有限公司、武汉译国译民教育科技有限公司

大赛具体事项如下:

一、赛事安排

1.报名及参赛时间

2023年6月18日——2023年9月10日。(8月中旬考试系统将进行升级,预计时长为1周时间,请合理安排时间)

2.参赛操作流程及注意事项

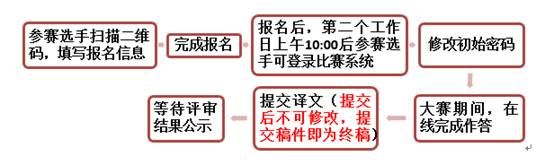

选手需先扫描打开下方二维码,按要求填写信息,完成在线报名。报名完成后,第二个工作日上午10:00后即可登录比赛系统答题。届时,请参赛选手根据提示,输入用户名及初始密码,登录比赛系统(伊亚笔译教学与语料软件:https://www.ventureoia.com/saipan/venture/home,支持Google Chrome、Firefox、Microsoft Edge、360浏览器极速模式,不支持平板、手机等移动端登录),修改初始密码后,重新登录系统,进入首页作业模块,选择相应组别试题,在线完成作答,并提交译文(提交译文后将无法更改,提交稿即为终稿;如暂不提交,请及时“保存”)。

【报名二维码】

【报名信息填写】在线报名时,选手须根据规范,自行设置用户名:用户名须包含6~16位字母或数字。初始密码888888。选手凭此用户名及初始密码登录比赛系统。

【报名咨询电话】报名过程中,如有问题,请联系徐老师(18627883831)。

【大赛系统技术支持电话】比赛系统使用过程中,如有任何技术问题,请联系许老师(15807198803)。

【大赛操作流程图解说明】

3.参赛译文提交注意事项:

(1)文档内容只包含译文,请勿添加脚注、尾注、译者姓名、地址等任何个人信息,否则将被视为无效译文。

(2)译文内容与报名时选择的参赛组别须一致,不一致视为无效参赛译文。如:选择参赛组别为英译汉,提交译文内容若为汉译英,则视为无效译文。

(3)2023年9月10日24时之前未提交参赛译文者,视为自动放弃参赛资格,组委会不再延期接受参赛译文。每项参赛译文提交后将无法更改,译文仅第一稿有效,不接受修改稿。

(4)为避免9月10日服务器过度拥挤,请尽量提前完成翻译,提交译文。

4. 大赛评审

大赛评审包括线上线下初评、复评和终评三个环节。我们将邀请从事中医

翻译教学研究的专家进行认真评审,确定最终获奖名单。

5.信息发布

2023年6月18日发布大赛启事及参赛方式,预计将于2023年9月30日(世界翻译日)公布获奖信息。

信息发布媒体:

中国外文局翻译院 (网址:http://www.caot.org.cn/);

湖北中医药大学外国语学院网站(网址:https://wyx.hbucm.edu.cn);

湖北中医药大学外国语学院微信平台(微信号:gh_ef4dc14d833d);

世界中联李时珍医药研究与应用专业委员会微信平台(微信号:gh_27579c5b0542)。

6.颁奖典礼及学术报告

请关注信息发布媒体,时间、地点和方式将另行通知。

二、参赛规则

1. 参赛形式:本届大赛分汉译英组(笔译)、汉译日组(笔译)与英译汉组(笔译)三组形式,汉译英与汉译日使用同一赛题资料。选手可只选其中一组,也可选择三组,同时获奖的选手将获得各相应的证书和奖品。

2. 选手范围:对选手国籍、年龄、学历等不作限制。

3. 组织纪律:参赛稿件须独立完成,一经发现抄袭,将取消参赛资格。自

公布大赛原文起至提交参赛译文截稿之日止,参赛者请勿在任何媒体公布自己的

参赛译文,否则将被取消参赛资格,并承担相应法律后果。

三、奖项设置

1. 个人奖(汉译英组)

特等奖1名获奖证书+奖品A

一等奖2名获奖证书+奖品B

二等奖3名获奖证书+奖品C

三等奖4名获奖证书+奖品D

优秀奖若干名

2. 个人奖(汉译日组)

特等奖1名获奖证书+奖品A

一等奖2名获奖证书+奖品B

二等奖3名获奖证书+奖品C

三等奖4名获奖证书+奖品D

优秀奖若干名

3. 个人奖(英译汉组)

特等奖1名获奖证书+奖品A

一等奖2名获奖证书+奖品B

二等奖3名获奖证书+奖品C

三等奖4名获奖证书+奖品D

优秀奖若干名

3.指导教师奖

特等、一等、二等、三等奖选手的指导老师可获得相应的指导教师奖(可无指导教师),并颁发获奖证书。

4. 优秀组织奖

大赛设优秀组织奖若干名,欢迎各单位积极宣传并组织参赛。

四、参赛费用

本大赛为大型社会公益性翻译赛事,无需缴纳任何费用。

五、联系方式

为确保本届赛事公平、公正、透明地进行,特成立大赛组委会,负责大赛的组织、实施、评审等各项工作。组委会办公室设在湖北中医药大学外国语学院中医药国际传播研究中心(X533办公室)。

联系人:

毛老师电话:139 8618 7098

王老师电话:150 7100 2200

黄老师电话:189 8611 6448

附件:

第五届“时珍杯”全国中医药翻译大赛原文

【汉译英/汉译日原文】

中医经典理论与临床实践

在外行看来,中医最适合用来治疗慢性疾病,或是人们常说的“西医治标,中医治本”。在目前的医疗实践中,在疾病紧急、危重的关键时期用西医治疗,而之后中医才介入治疗,承担收尾工作并提供后期的护理。人们认为中医只能治疗非致命性的疾病。

在过去的十年或更久以前,许多人提出了以下问题:中医能否解决临床中遇到的问题?在任何科学领域,都是理论走到实践前面,而实践随之发展。然而近几十年来,每当患者出现高烧不退的症状,最终都会接受抗生素治疗。这是否反映了中医理论的陈旧和落后,致使其无法为现代医学的临床实践提供有用的指导呢?如今中医的临床实用性相对不足,临床医师对中医的期望值也不高,这些是否表明中医的核心理论真的存在缺陷呢?

针对任何类似上述的观点,我都持相反意见。我坚信,中医理论一点都不过时,也不落后。它实际上遥遥领先于时代。中医理论和一些其他的传统技艺一样,都具有这种特点。近代著名哲学家梁漱溟指出,中国的传统文化如儒家、道家和佛家,可归类为人类学上早慧的文化结晶。我认为,中医也是如此,并且它的成熟程度即使在当今也很先进。

现代社会对中医理论的理解肤浅且过于简单。人们审视中医犹如某些世故的城里人看待山区的朴实农民一般。只有回归简单,我们才能回归到真实。如果你还没有真正理解中医理论,或者至少尚未大致领悟其要领,又有何依据判定它原始还是先进呢?

每当某一方剂对患者不奏效时,我从未怀疑是中医或中医理论出了问题。反而,值得反思的是当代人认为中医理论落后于临床实践这一看法。今后,当我们所开的药方效果不佳时,我们要在自身对中医的领悟上找问题,而不是归咎于中医理论。

传统中医理论的应用几乎完全依靠医师的主体感知和号脉诊断。这取决于医师对直接感知的掌握程度和阐释这种感知的能力。我们应该以极其清醒的头脑来应对有关经典中医理论的任何问题,并扪心自问:如果中医有任何缺陷,是理论本身存在问题,还是周围环境造成了问题。

【英译汉原文】

The Impacts of Li Shizhen’s Bencao Gangmu

The context in which the Bencao Gangmu was compiled plays a large role in the wider story tracing humankind’s curiosity with the natural world. Europe’s scientific culture in the early modern period became incommensurable to that of the East by the 17th century, and 20th century historiography has marked this as the rise of European intellectual history. Practices of knowledge exchange became central to scientific thought, particularly the dissemination of various astronomical theories between Europe and the Ottomans. However, little has been said about the rise of natural history in China and its impact in a global context. This too was a product of the early modern transformation of science, which – just like in Europe – had been made possible by the diffusion of science into the wider public sphere, and the increased accessibility of scholarly texts for the literate. The print market of the late Ming provided this new textual landscape at “ridiculously low prices”, according to the Jesuit Matteo Ricci. As well as the increase in available texts, new objects had begun to be documented in the medical canon due to increased trade networks and a new demand for exotica. As a result of these factors, natural history emerged in China and notably, Li’s Bencao Gangmu entered Japan in the 17th century. The subsequently institutionalized knowledge of nature in pre-modern Japan depended largely on this canonical text, which initiated the study of nature in Tokugawa Japan.

Given the status of natural history in the early modern period, it is of no surprise that the ambitious Li Shizhen embarked on a pursuit of the “broad learning of the things” (bowu). His pursuit was largely based on observation, as he claimed to have personally consumed remedies to check their qualities, and this was a common practice among physicians. However, he also adopted an approach different to his naturalist predecessors. Li understood that the natural world was in a constant state of flux, or transformation, and that it was necessary to account for this when harvesting flora or fauna for medical use, for example. In order to pinpoint normal patterns of change that existed in this natural world, Li used epistemically varied sources, alongside his own learnings of how the world operated, to create a generalized and abstract image of how bodies work within a universe of metamorphoses and transformation. Thus, he spent thirty years travelling across southern China in order to gather these sources for his medical encyclopedia; he interviewed farmers and hunters, performed experiments, treated patients and extensively read previous naturalist works. By 1561, Li returned to his home region of Qizhou and began to synthesize everything he had learned in his garden house on Rain Lake shore. This period of change, in which his adventure as a “crusader of knowledge” shifted into a time of reflection and writing, was marked by his decision to change his name to Binhu – little did he know that his adventure was far from over. Once he had finished constructing his Bencao Gangmu in 1587, at the age of 72, he was not able to convince a printer at the Nanjing print market to publish the several million-character long manuscripts he had dedicated his life to. Subsequently, he visited his acquaintance Wang Shizhen in Taicang, with the hopes that this scholar-official would be able to endorse his work. Li was eventually left satisfied after obtaining Wang’s preface and the man’s word that a printer, Hu Chenglong, would publish his work. Unfortunately, Li died in Hubei before he could oversee the publication. Nonetheless, Wang certainly paid sufficient homage to his friend, describing Li’s vast scope of work: “Like entering the Golden Grain Garden, the varieties of colors dazzle the eyes.”

What was unique enough about the Bencao Gangmu that it could be granted the title of a “dictionary of Chinese knowledge”? The text reorganized natural knowledge systematically through (1) the standardization of species names; and (2) the hierarchical classification of species. Regarding the latter, Li separated natural specimens into minerals, plants and animals, and distinguished them from the pharmacological substances developed from them. While he categorized various medicinal substances according to the disease they allegedly cured, his systematic taxonomy of species was concerned with the division of species into groups called gang and smaller categories called mu (hence using the name gangmu to denote this hierarchical organization). The 52 chapters (juan) of this work is also structured in an orderly manner, moving from the most fundamental natural objects (water, air, earth and fire) to plants and animals, and lastly to mankind. Notably, much of the text is on disease and the natural history of known drugs, which were also categorized, this time in accordance with their qualities such as flavor (wei), toxicity (du), or presence of heat and seasonality. Thus, his materia medica was considered in the Ming dynasty to be an exegetical text – one with an impressive breadth of classifications that synthesized all known Chinese medical and natural knowledge.

Li Shizhen’s materia medica remains an important source for the research of traditional Chinese medicine. The historical uses of the medicinal plants of China were confirmed by the scientist Tu Youyou, who was rewarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2015, and used the Bencao as a prime source for his research. There has also been more recent research in identifying Chinese medicinal plants in the medicine of the Mediterranean world in Antiquity using Li’s work. For example, a comparison between the therapeutic uses of Chinese plants by Li and the earlier text Dioscorides suggest that these plants may have been introduced into the Mediterranean regions as early as the first century BC. Therefore, it is possible that cross-cultural interactions between the Chinese medical tradition and wider parts of the globe existed well before the early modern world, probably reaching the Mediterranean through trade with Indian markets, since this area of contact along with the Black Sea corresponds to the south and north routes of the Silk Road. It is evident that this medical encyclopedia will always remain an important body of text in the natural history framework, and therefore we must continue to study its contents and how it influenced the wider world in the early modern period.